Development history of electrolyzer stack

Release time:

Nov 02,2021

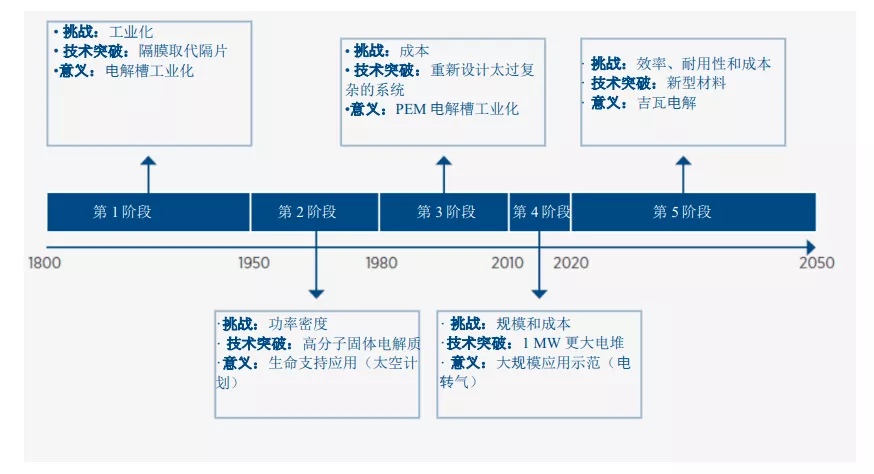

The use of electrolysers has been popular for more than two centuries. Although the basic technology remains the same (as shown in the figure below), different trends have affected the development of the electrolyzer, which is roughly divided into five stages.

Phase 1 (1800-1950):

Electrolytic stacks are mainly used for hydropower (low-cost power generation) to produce ammonia. By 1900, more than 400 industrial electrolysers were in operation (Santos, Sequeira and Figueiredo,2013). Electrolytic stacks for this purpose are also used in Norway, Peru, Zimbabwe and Egypt. Alkaline electrolyzers were the only technology used at the time. The cell operates at atmospheric pressure using a concentrated corrosive alkaline solution such as potassium hydroxide [KOH], using asbestos as a gas barrier (called a diaphragm). Asbestos can cause great health hazards, but this was not known until the end of the 20th century, so other materials have been used to replace asbestos (such as ZIRFON®). Although there was initially no better alternative, from the middle of this century, composite zirconia (ZrO2) isolation layer has become a trend. Towards the end of this generation, Lonza (and later IHT) was first introduced into a pressurized alkaline cell system in 1948. The electrolyte is also used to produce chlorine, a process that uses the same electrochemical principles but uses highly concentrated sodium chloride dissolved in water as a feedstock and produces hydrogen as a by-product. This is an important application scenario for electrolysis that emerged in the early 19th century.

Phase 2 (1950-1980):

The electrolyzer achieved a breakthrough in polymer chemistry in the last few years of the previous phase, marking the beginning of phase 2. In 1940, Dupont discovered a material with excellent thermal and mechanical stability, which also has ionic properties (meaning good proton passability). This material is the basis of a PEM electrolyzer. PEM cells can be simply injected with pure water instead of the caustic solution in alkaline systems, which greatly reduces the complexity and carbon footprint of the system, and improves efficiency and power density. General Electric was one of the pioneers in the development of PEM electrolyzers, followed by Hamilton Sundstrand in the United States and Siemens and ABB in Germany. The deployment and learning activities of PEM electrolysers are mainly driven by the needs of spacecraft projects (such as Gemini) and submarine military life support systems.

Phase 3 (1980-2010):

With the end of the space race, other commercial opportunities must be found for the PEM electrolyzer. This requires greatly simplifying the design, reducing costs, and increasing the stack size to several hundred kilowatts. The results of these changes include improved system efficiency, lower capital costs, and a lifespan of more than 50000 hours. In terms of alkaline electrolyzers, large-capacity units combined with hydroelectric power generation equipment must be redesigned into smaller pressurized stacks in order to be introduced into applications with low hydrogen demand.

Phase 4 (2010-2020):

Three major trends emerged from this phase. First, installed PV and wind capacity increased by 14 and 3 times, respectively, during this period, and the costs of PV, onshore wind and offshore wind fell by 82%, 47% and 39%, respectively (IRENA,2020a). This has led to a significant reduction in the main cost factor for green hydrogen (I. e., electricity), which has increased the commercialization of green hydrogen. Second, climate change has become increasingly important on the political agenda. This provides support for decarbonization of industries other than power generation. Third, the increasing capacity of advanced electrolyser stacks has reduced the capital expenditure on electrolysers (CAPEX), thus putting green hydrogen on the energy policy agenda.

Phase 5 (after 2020):

It is expected that during this period, the electrolyzer will move from a niche market to a mainstream market, from a megawatt to a gigawatt scale, and the possibility will gradually become a reality. The objectives of this phase include cost reduction (<$200/kW), improved lifetime (> 50000 hours) and improved efficiency (close to 80% ,LHV). But the implementation of this goal requires economies of scale, increased production capacity and technological breakthroughs through research.

Key words:

Related News